Agent Framework Philosophy: The Unbitter Lesson

1. Introduction: The Burden of Abstraction

The history of software is a history of abstraction. We build layers to hide complexity, creating frameworks, patterns, and objects that promise to make our lives easier. Yet, in the nascent field of agentic AI, this instinct has led us astray. Early attempts at agent frameworks are replete with complex class hierarchies, managers for every conceivable concept (Memory, Task, Tool), and intricate state machines. They are monuments to premature abstraction.

As Gregor Zunic (Cofounder & CEO of Browser Use) puts it, these frameworks fight the very nature of the intelligence they seek to orchestrate [1]. They fail not because the underlying Large Language Models (LLMs) are weak, but because their rigid structures impose a human-centric view of reasoning onto a non-human intelligence. They encode assumptions that are immediately invalidated by the next model breakthrough.

This document outlines a different philosophy, one derived from first principles and validated by the hard-won lessons of industry pioneers like Anthropic, Manus, and OpenAI [2][3][4]. It is a philosophy of radical simplicity, where we seek not to build an agent, but to unleash one.

2. The First Principle: An Agent is a Loop

If we strip away all the noise, what is an agent? It is a process that perceives, thinks, and acts, in a cycle, to achieve a goal. In the context of LLMs, this translates to an almost trivial implementation:

An agent is just a for-loop of messages. The only state an agent should have is: keep going until the model stops calling tools. You don’t need an agent framework. You don’t need anything else. It’s just a for-loop of tool calls. [1]

This loop is the universal constant of agentic systems. It is the engine. Everything else is just fuel and scenery.

# The irreducible core of an agent

while True:

response = llm.invoke(context, tools)

if not response.tool_calls:

break

for tool_call in response.tool_calls:

result = execute(tool_call)

context.append(result)

Our entire architectural philosophy is built upon the foundation of protecting and empowering this simple loop. We must resist the urge to complicate it.

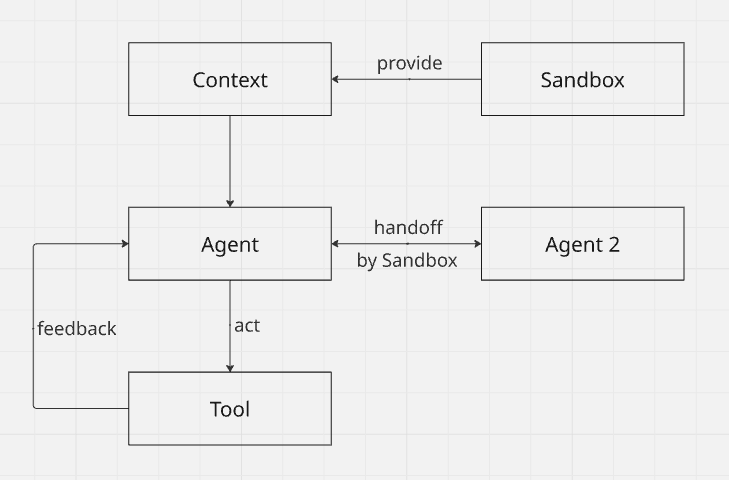

flowchart TD

Sandbox -->|provide| Context

Context --> Agent

Agent -->|act| Tool

Tool -->|feedback| Agent

Agent <-->|handoff by Sandbox| Agent-2

3. The Three Pillars of Simplicity

Our design is guided by three core tenets that emerge from observing what works in practice.

Pillar I: The Sandbox is the World

Instead of creating a multitude of objects to represent the agent’s world (Project, Task, Memory, Files), we unify them into a single, holistic concept: the Sandbox. The Sandbox is an isolated execution environment, typically a virtual machine or container, complete with a file system and the ability to run processes.

This is the most profound simplification. The Sandbox is the state.

- Memory is the File System: An agent’s memory is not an abstract class; it is the collection of files within its sandbox. This provides an unlimited, persistent, and directly operable memory that the agent can structure and manage itself, a technique proven effective by Manus [3]. The agent learns to write notes, create logs, and manage data just as a human would.

- Context is the Sandbox’s History: The

contextpassed to the LLM is simply the append-only log of what has happened inside the sandbox—a stream of actions and observations. - Projects and Tasks are Implicit: A project is not a database entity; it is a directory in the sandbox. A task is not an object to be managed; it is the initial prompt that kicks off the agent loop.

By unifying the agent’s world into the sandbox, we eliminate dozens of unnecessary classes and the complex interactions between them. The agent interacts with its world not through abstract methods, but through concrete tools like shell and file.

Pillar II: An Agent is a Configuration, Not a Class

Traditional frameworks encourage a deep inheritance model: BaseAgent gives rise to ConcreteAgent, which is then subclassed into SoftwareAgent, ResearchAgent, and so on. This is a fallacy. It conflates an agent’s identity and capabilities with its implementation.

In our philosophy, an Agent is merely a configuration. It is a plain-text or JSON object that defines two things:

- Instructions: The system prompt that tells the LLM its role, personality, and objectives.

- Tools: A list of capabilities it is allowed to use.

The AgentRunner—the engine that executes the core loop—is stateless. On each iteration, it loads the current agent’s configuration, invokes the LLM, and executes the resulting tool calls. An agent is not an object; it is a mode of operation for the runner.

This approach has powerful implications:

- Simplicity: There is no

Agentclass to maintain. Adding a new agent is as simple as writing a new configuration file. - Flexibility: Agents can be composed, modified, and switched dynamically. Multi-agent collaboration becomes trivial: it is simply one agent using a

handofftool to tell the runner to load a different agent’s configuration on the next loop iteration [4]. - Transparency: The agent’s entire

definition is explicit and human-readable, making it easy to debug and understand.

Pillar III: Start with Maximum Capability, Then Restrict

Many frameworks begin by offering a small, “safe” set of tools, forcing the developer to add capabilities one by one. This leads to what has been termed the “incomplete action space” problem [1]. The agent is limited not by the model’s intelligence, but by the developer’s foresight.

We invert this. We start from the assumption that the agent should be able to do anything a human can do within the sandbox. We provide powerful, general-purpose tools from the outset: shell, file, browser. The agent has maximal freedom.

Restrictions are then applied as a layer of safety and guidance, not as a foundational constraint. This is the principle of “Mask, Don’t Remove” articulated by Manus [3]. We don’t take tools away; we temporarily make them unavailable based on the agent’s current state or task, guiding the LLM’s attention without crippling its potential. This ensures the action space remains complete and the KV-cache remains intact, preserving performance and adaptability.

4. Conclusion: The Unbitter Lesson

The bitter lesson of AI research is that general methods that leverage computation ultimately outperform systems based on hand-crafted human knowledge. Agent frameworks are at risk of repeating this mistake by encoding too many assumptions into their design.

By embracing radical simplicity, we learn the unbitter lesson: the most powerful agent framework is the one that gets out of the way. It is a minimal, stateless loop engine operating within a unified sandbox. It treats agents as simple configurations and trusts the LLM to be the intelligent, reasoning core.

This philosophy is not about building less; it is about building right. It is about creating a foundation that is not brittle but resilient, not complex but elegant, and that scales not in spite of, but because of, the relentless advance of AI.

References

[1] Zunic, G. (2026, January 16). The Bitter Lesson of Agent Frameworks. Browser Use Blog. Retrieved from https://browser-use.com/posts/bitter-lesson-agent-frameworks

[2] Schluntz, E., & Zhang, B. (2024, December 19). Building effective agents. Anthropic. Retrieved from https://www.anthropic.com/research/building-effective-agents

[3] Ji, Y. (2025, July 18). Context Engineering for AI Agents: Lessons from Building Manus. Manus Blog. Retrieved from https://manus.im/blog/Context-Engineering-for-AI-Agents-Lessons-from-Building-Manus

[4] OpenAI. (2024). Orchestrating Agents: Routines and Handoffs. OpenAI Cookbook. Retrieved from https://developers.openai.com/cookbook/examples/orchestrating_agents/